By Rafael Pedemonte

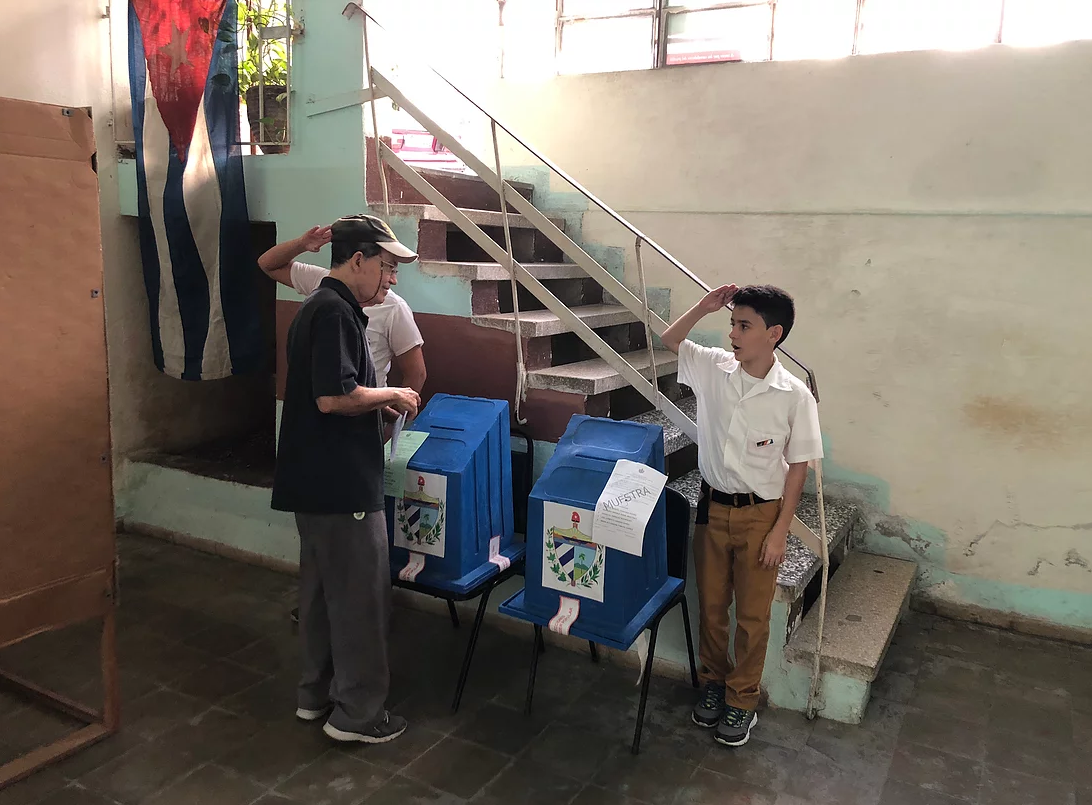

Parliamentarian elections were recently held in Cuba (March 2018). Well, to call them elections may be a matter of controversies. 605 names appeared in the ballot papers for a “National Assembly of People’s Power” made up of… 605 members! I was in Havana when elections took place, and moved to the closer polling station barely ten meters from where I was staying. One of the reasons explaining massive participation in elections is the ability to mount numerous polling station, allowing people to vote just a few steps from their house. I observed with great amazement nearly all my neighbors complying with their civic responsibility, even those who don’t hide from me their strong opposition to the Cuban political system. Most of them validated the entire list of candidates, a common practice, and, after few minutes of friendly chatting, returned to their flats where nothing would really alter the normal unfolding of Sunday afternoon in Havana. I experienced no obstacles to witness the electoral process and I was even able to take a photo with two pioneers (pioneros) casting simultaneously a military salute. It was, however, impossible to attend the vote counting that I could merely observe from far away, through an opaque window.

Not surprisingly, the 605 candidates obtained more than the 50% threshold, thereby integrating the legislative parliament. This is the political body that, few weeks later, unanimously approved Miguel Díaz Canel’s installation as the first non-Castro president since 1976.

Who is Díaz Canel and why is his nomination seen as a historic event?

First, he is “young” (aged 57) in comparison to Raúl Castro (aged 87), former President, brother of the Líder Máximo, Fidel, and a key actor of the revolutionary insurrection since 1953. Díaz Canel has faithfully followed the traditional “political itinerary” within the Cuban Communist Party. He first committed himself to the Communist Youth, before being appointed First Secretary of the Provincial Party Committee of Villa Clara Province. There, he maintained an orthodox political stance, but evinced a liberal position when it comes to moral issues, allowing for example the opening of the LGTB cultural center El Menjunje. After moving in 2013 to the Holguín province, he became Minister of Higher Education and First Vice-President of the Council and, eventually, President. Expectations regarding his widely anticipated nomination were somehow tainted at mid-2017, when a videotape of a private meeting of the Communist Party was leaked. In it, Díaz Canel revealed a hardline tone, accusing independent media and dissidents (“mercenaries”) of supporting subversion with U.S. assistance.

It has been stated that the “old generation” is handing power over to a renovated leadership, whose intentions have become a matter of multiple speculations. But are we facing the watershed moment that some observers herald? At least in political terms, the 2018 elections announce more continuities than major institutional and ideological changes. To fully understand Cuba’s inner balance of power it is required to take a glimpse beyond the Council of Ministers. As in the former USSR, and virtually all Communist countries prior to 1991, the government, hence the President, doesn’t really embody the main political authority. The Communist Party is the supreme body, “the leading force of society and of the state”, as stated in the Cuban 1976 Constitution. Raúl Castro is the First Secretary of the PCC since 2011 and would remain in this position until 2021, unless laws of nature determine otherwise. He is escorted by the First Vice President José Ramón Machado Ventura (aged 87), Machadito for Raúl Castro, with whom the brother of Fidel built a lasting friendship since the time they were fighting together in the Sierra Cristal (1958-1959). Beyond that, Raúl Castro also controls the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces (an organization considerably strengthened since Fidel Castro’s gradual retirement in 2006). Therefore we must assume that the expected relegation of the “old generation” is not yet to come.

It is clear that crucial decisions are still in the hands of Raúl Castro and his comrades from the time of the Sierras’ struggle. The ongoing discussion over constitutional reforms clearly indicates so. The plenary meeting of the National Assembly of the 2nd of June 2018, was announced by some as “historic” but was finally reduced to a monotonous ratification of a series of topics seemingly determined “from above”. Constrained by the orientation of the “real power” in the shadows, Díaz Canel, his ministers and the legislative body are not expected to load the current debate with an unforeseen dose of innovation.

Even in the Council of Ministers, the equivalent of a Cabinet, the “heroes” of the insurrection against Batista have not been completely replaced. Keeping a severe eye on his pupil’s actions, Ramiro Valdés (aged 86) has proved to benefit from an exceptional physical and mental agility, being assigned one of the Vice Presidency of the Council. Already in 1953, Ramiro Valdés played a significant role by recruiting potential fighters in the city of Artemisa for Fidel Castro’s movement. Later, he took part in the legendary 1953 Moncada Attack (the “Cuban Bastille”) where he was injured. He was appointed Minister of Interior, first from 1961 until 1968 and then from 1979 until 1985. Apart from Raúl Castro, it is hard to point to a more remarkable figure of the Revolution. It is certainly no coincidence that such a mythical revolutionary has been granted the responsibility of representing the “old guard” within the newly renovated government.

This is of course not to say that no changes will be introduced.

A steady opening to foreign influences is perceived as an unavoidable result of growing access to Internet. Access still costs a Cuban dollar per hour, a hardly affordable price for the meager Cuban salaries but an improvement comparing with the 4,5 dollars that an hour costs four years ago. Together with Internet penetration, the web is offering more open press alternative as Oncuba.com, which, although prudently critical, contrasts with the monotonous and propagandistic style of the official newspaper Granma. Society is now likely to get acquainted with more controversial opinions. Debates tackle issues that are currently under review within the Cuban government itself, such as whether to expand touristic activity or to allow private entrepreneurs to invest in a wider range of fields. Authorized “alternative” medias framed their content in some polemic issues, but is it hard to find by official means a structural attack on the political system or on the “sacred” legends of the revolutionary narrative.

One of them is José Martí (1853-1895), whose name is engraved in the Constitution as main guide for the revolutionary consciousness. The second and more recent “untouchable reference” is, since the first hours of his death in November 2016, Fidel Castro, purposely buried next to Martí in Santiago. Drinking alcohol, live concerts and performances were forbidden during the period of mourning which stretched out over almost 10 days. I was astonished to observe in February 2018 an unrelenting proliferation of the image of Castro in virtually every public building, commonly accompanied by Fidel Castro’s definition of the concept of revolution, which I ended up learning by heart…

Revolution means to have a sense of history; it is changing everything that must be changed; it is full equality and freedom; … it is challenging powerful dominant forces…

Regarding Martí, a controversy has recently ringed the alarms, recalling to the community what is still a matter of stern official veto. The film Quiero hacer una película was blocked during a youth festival (Muestra Joven) by the official ICAIC (Cuban Institute of the Art and Film Industry) for referring to Martí in a “disrespectful way”. That may be deemed a rather symbolic episode, but it reflects that, although a gradual opening can be hinted, there is still a thick line that cannot be overstepped and that the first years of Díaz Canel in power would seemingly not push back.

*An extended Dutch version of this article will be published in Vrede. Photo: Rafael Pedemonte.